Col du Granon

After a somewhat perilous, 25 minute, hair pin drive, climbing high above the Serre Chevalier Valley and Chantemerle, where we’re hoping to ski next year, we arrived at the Col du Granon. We’d been recommended to go there to hike but had no idea about the history in les Hautes-Alpes we were about discover. And I have to confess, as the mountainside fell away, with sheer drops to our side and at times a sever lack of roadside barriers, I was not sure this was such a good plan. My driver of course had other ideas, clutching the steering wheel determinedly as if he were in a James Bond movie.

At every twist and turn, the scenery, dressed in a vibrant gown of gold and umber, was stunning.

When we finally reached the summit, we found ourselves on a surprisingly vast, flat plain, surrounded by breathtaking mountain scenery, I had to begrudgingly admit that it had been worth the jaw clenching moments! It felt like we were on top of the world and at 2413 meters, almost 8000 feet, we were, almost at the same altitude as the peaks we ski at in Lake Tahoe.

The expansive views back across the Serre Chevalier Valley revealed the ski terrain we’re hoping to conquer, seemingly not too intimidating for a somewhat ‘cappuccino skier’ like myself!

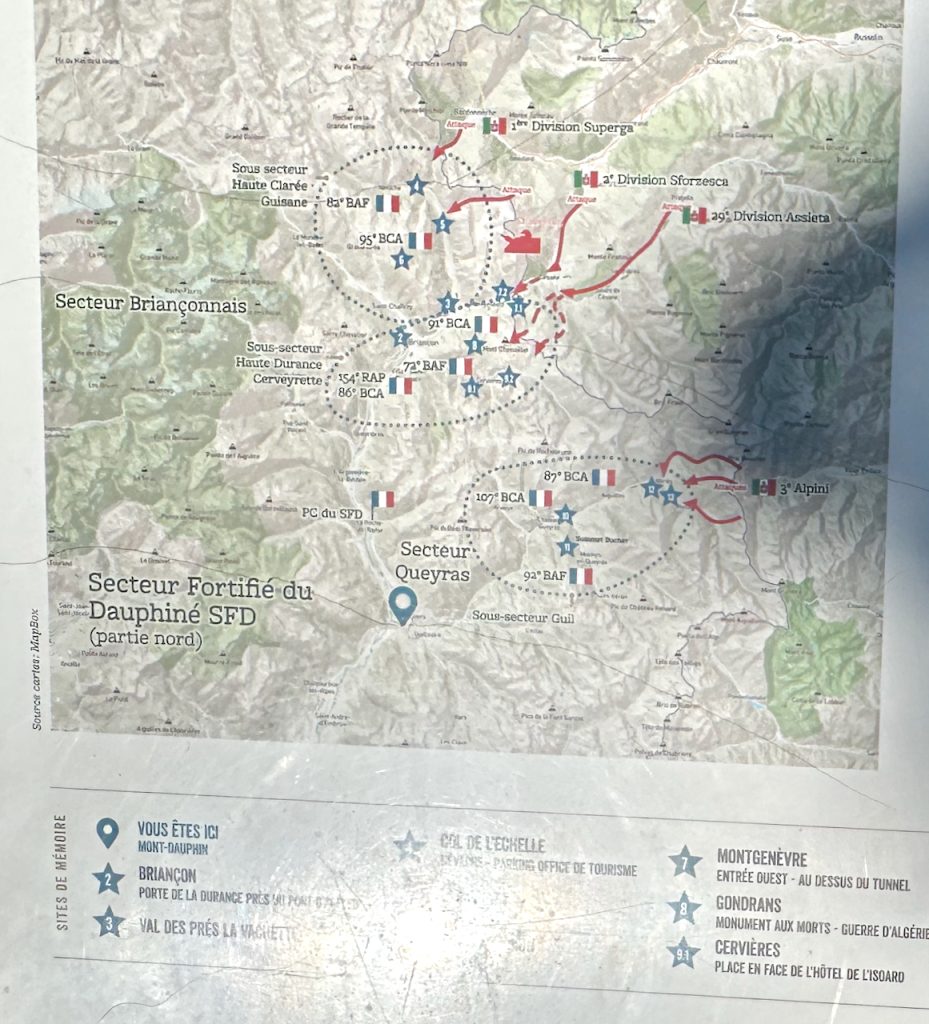

Across the other side of the wide area where we’d parked was a huge ravine overlooking another series of mountain peaks. And once we’d read the information board we realised that these mountains were in Italy and that we were standing on a World War II Defense System around the Col du Granon.

Memory Trail in Briançonnais

We were overlooking the Clarée Valley, which stretches from the Col de Buffere to the Peyrolles Ridge and ends at La Vachette. In June 1940, the Italians had made an advance across these mountains with the intention of capturing southern France. They had built combat positions below L’Aiguille Rouge above the Col de l’Echelle.

During our drive up to the summit, just before we’d arrived at the top, we’d passed an impressive number of military looking buildings, shelters, and blockhouses. From where we were now standing, looking at the Italian mountains, these were slightly down the mountainside behind us.

During WWII the units of the Alpine 47th Half Brigade (DBCA) had been deployed here to defend this line.

The Italians never got this far, they were stopped on the line of outposts at Col de l’Echelle, Plampinet, Col de Montgenevre, Gondrans, and Cevieres. A battery from the 93rd Artillery Regiment (RAM) had intervened on June 16th from the L’Oule Valley, having been deployed from Chantemerle on June 15th to 16th to intervene against the Italians. Only the artillery fired from this line. On June 17th and 18th, the French soldiers stopped the infantry attacks at the Col de L’Echelle itself.

Passing fallen rock piles, shattered by the force of nature not artillery, I could almost hear the gunfire. What must have it been like to be defending your country’s frontier from such perilous heights? And at such a desperate time when the free world was spinning rapidly out of control. What would have happened if Italian soldiers had been victorious, marching into the sleepy alpine villages of Serre Chevalier……….?

Col du Granon Tour de France

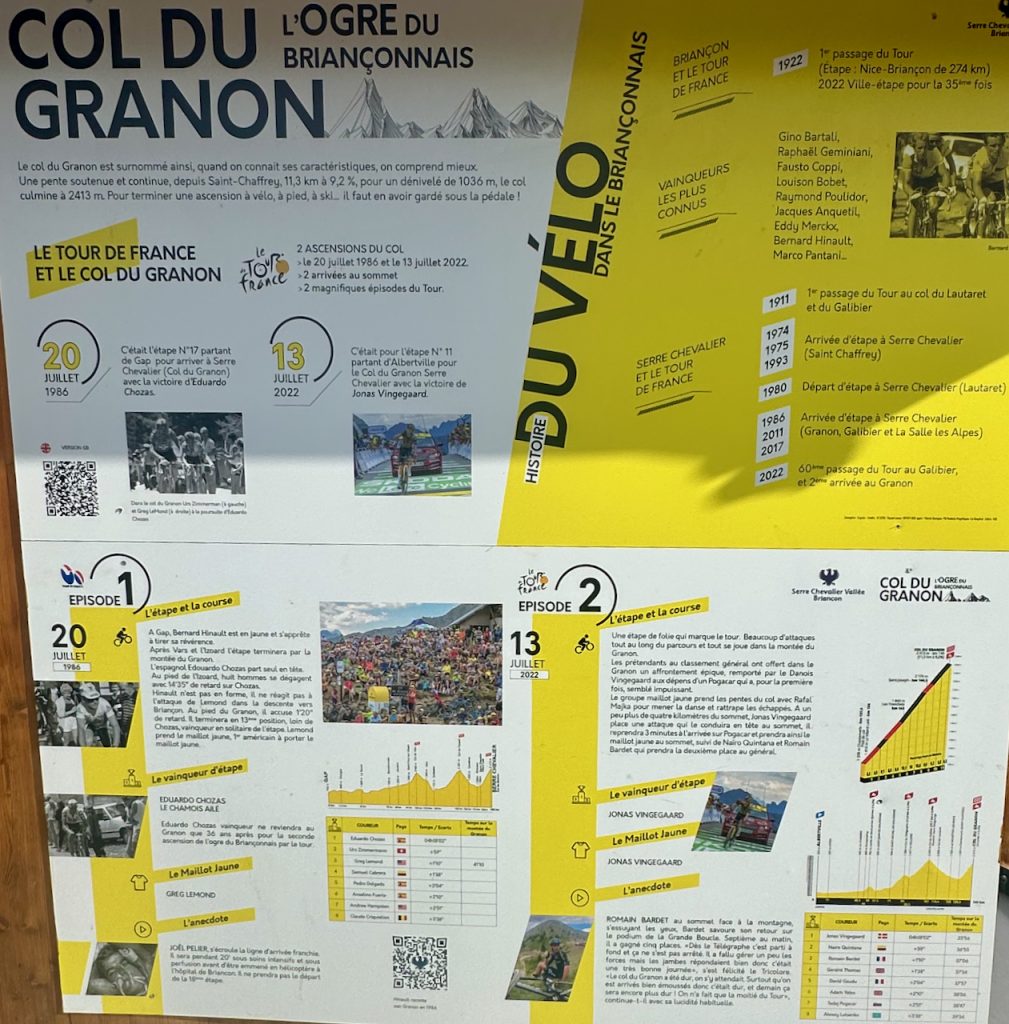

As we made our way back to our car we discovered more recent, much less sinister but also spectacular events had taken place here. In 1986 and 2022 Col du Granon had been one of the summits conquered by the valiant cyclists of Le Tour de France.

On 13 July 1986, this had been stage number 17 of Le Tour de France, it had started from Gap and was won by Spanish, Eduardo Chozas. On 20 July 2022 it had been stage number 11, starting from Albertville and won by Danish, Jonas Vingegaard

Mont Dauphin

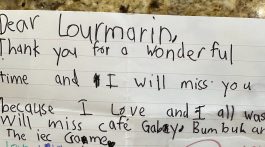

The following morning we were returning to Lourmarin but not before we made one more stop. Just under an hour away, 40km (25miles) south of Briançon, the UNESCO heritage site, Mont Dauphin, was waiting for us. Another one of Vauban’s fortified garrison towns and more history in Les Hautes-Alpes

The Lunette d’Arçon at Mont-Dauphin

All we could see when we first arrived were the ramparts of the fortifications where the Lunette D’Arcon was immediately prominent. When it was designed by Vauban in 1693, this large promontory had been the only point of access without any natural defense. Vauban therefore created a defensive system on this side in the form of a bastion front. This made it possible to be able to fire on assailants moving towards the garrison from the open terrain in the forefront. It was constructed between 1728-1732 and modified in 1792 in line with General Arcon’s design principles.

This lunette was a defensive structure jutting out from the surrounding wall which made it possible to see any potential assailants from far away and be able to initiate the necessary defenses far sooner than otherwise might have been possible.

It was shaped like a pentagon with 2 large sides and wings, a central tower and casemate in the curve to make it possible to attack assailants from the rear. The lunette was connected to the ditch by an underground passageway.

As we made our way through these defenses we could see the glimpses of the garrison town it had been built to protect.

We entered this inner fortress town through its’ large outer gates.

Here there were outhouses similar to those we had seen in Briançon’s Cité Vauban.

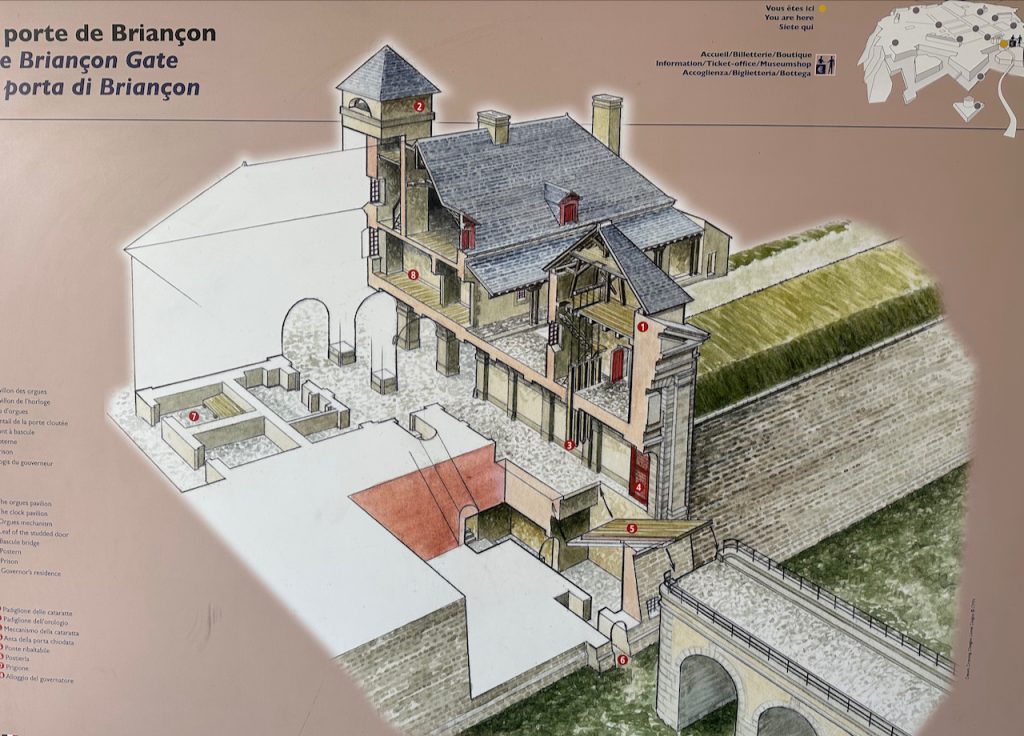

We approached the entrance at the Briançon Gate, the largest of the two entries,

It was protected by a drawbridge and a studded door and once we’d passed under its domed archways we were inside the garrison town.

On the ground floor of the Briançon Gate there was a forge, prison and the guards’ room. From here steps descended to the bascule pit of the bridge. The clock, originally intended for he church was installed in 1821.

Diagram of the Briançon Gate

The impressive Le Pavillon des Officers, was to our right. It had been built between 1693 & 1700 to accommodate the general staff and governor of Mont Dauphin. Surprisingly, it is possible to still stay in Le Pavillon today.

Immediately ahead of us was the main street, Rue Catinat. The houses here had been built in a homogenous style with plain facades and arched doorways. Living spaces were on the upper floors and shops on the ground floor opening out onto the street via their wide archways. In the 19th century the civilian population reached a peak of 400 with the same number of soldiers, five times fewer than Vauban intended. We were surprised to see a great deal of renovation work to preserve the town for those that still live and work here today.

The grain measure used during markets and fairs can still be found and the ‘fountain of the four corners’.

The shopping street of Rue Catinat was crossed at right angles by Rue Cabrieé, which remains home to local artisans.

Church L’église Saint-Louis, Mt-Dauphin

The church was built around 1700. It too was designed by Vauban and like those in his other fortified cities it was built to demonstrate the strength of royal power and Catholicism in Louis XIV’s France.

Constructed from local pink marble, the church was originally designed to be 45 metres (148 feet) long by 18 meters (59 feet) high. However, financial constraints meant only the choir, sacristy and lower part of the bell tower were ever completed.

The Arsenal

The Arsenal was an impressive building and originally housed a store of guns & cannons which corresponding to the number of soldiers stationed here.

Canons and artillery were stored on the ground floor, flintlock, rifles, cold weapons and munitions on the upper floor. The Arsenal was built on the edge of the surrounding wall, high above the River Durance below a steep wall, difficult to reach from the river.

The Arsenal was constructed between 1700 to 1750.

An outer wall protected its access into the Arsenal courtyard.

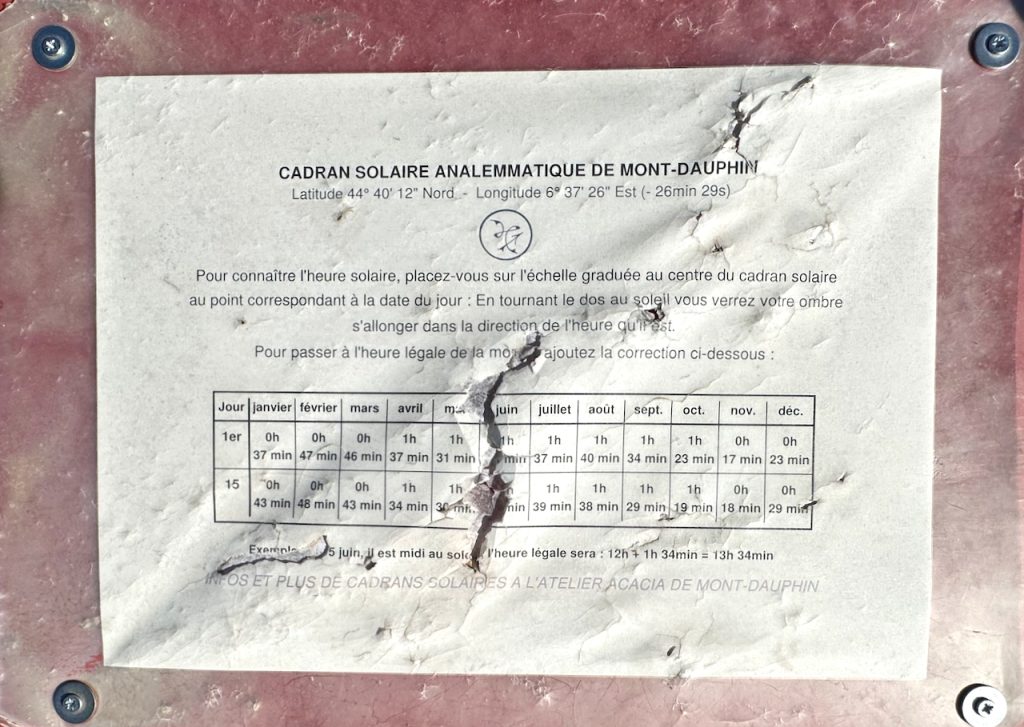

In the center of the Arsenal courtyard sits an imposing Sundial.

Ironically Mt Dauphin only witnessed one act of war, and that was years after its construction. Like Col du Granon, Mt Dauphin had been part of La bataille des Alpes‘. As we’d already discovered, this had been an incredible victory for the French mountain troops in June 1940 yet it remains a little known story of World War II.

We learned that there are in fact several other World War II sites near Briançon known as Briaçonnais situated along two defense lines that were occupied in 1940 by French military. They are marked by blue stars on the map above. In the Hautes Alpes, two sectors – Haut Claree/Guisbae and Haute Durance/Cerveyerette – and a reserve sub-sector at the Fort d’Anjou near Briançon.

On 10 June 1940, Mont Dauphin suffered the only bombardment in its’ long history when an Italian plane dropped its last bomb returning from a mission. It exploded 76mm shells that were in the Arsenal, destroying the oldest part of the Arsenal and starting a fire. Before the bombing, the Arsenal had consisted of two L-shaped buildings.

We’d been expecting to learn more 17th century history at Mt Dauphin, not a more ‘recent’ World War II story. On a peaceful, autumnal day this over eighty year old history seemed so far removed, yet this is history you can touch, the war of our grandparents, not so long ago…..

We finally tore ourselves away from this serene, historic place, where its’ autumnal colors were splashed against an azure, blue Provence sky. We’d come to discover Les Hautes-Alpes dreaming of skiing and left excited by the prospect but having learned so much more.

As the French say à la prochaine ~ until the next time.

No Comment