War; tragic and horrific.

Creating desolation, carnage and destruction.

Causing immense suffering, misery and loss,

destroying and changing lives forever.

Singapore during World War II was thought to be an impregnable fortress.

When it fell to Japan on February 15th 1942 it was probably Britain’s most humiliating defeat.

What followed were three and half years of hardship and cruelty.

No more so than at Changi …..

Entrance to Changi Museum and Chapel

A visit today to Changi Museum and Chapel is a solemn reminder of the evils of war. Most of the original gaol has been demolished, the museum and chapel remain to tell the story of what happened there after the Japanese capture of Singapore in 1942.

In 1942 Changi Gaol was a civilian prison on the Changi Peninsular, the British Army’s military base in Singapore, part of which included a collection of military barracks. Once the Japanese took control these barracks were used as prisoner-of-war (POW) camps and eventually any references to anyone of these camps just became ‘Changi’. Over 40,000 Allied troops were imprisoned here, mainly in the former Selarang Barracks. Most were then sent to work as slaves in Japanese occupied territories such as Sumatra, Burma, and the Burma-Thai railway. Thousands of civilians, mostly British and Australian, were imprisoned one mile away from Selarang in Changi Gaol. During the Japanese occupation in addition to the troops that were sent to Changi Gaol, over 3000 civilian men, 400 women and 66 children were incarcerated there, crammed together in terrible living conditions often tortured and beaten. The average living space per adult was 24 square feet, room barely enough to lie down. It became a living hell.

The original door way to Changi Gaol

Initially the Japanese seemed indifferent to what the prisoners did in Changi Gaol and the other POW camps. Concerts were organised along with quizzes and sporting events, although a meticulous military discipline was maintained.

Changi Gaol Artifacts

However, after Easter 1942, attitudes changed following a failed POW escape at the Selarang Camp. The Japanese demanded that everyone sign a document declaring that they would not attempt to escape. When this was refused over 15,000 POW’s were herded into a barrack square and told that they would remain there until the order was given to sign the document. When this failed a group of POW’s were shot. Despite this, no-one signed the document. Only when the Japanese refused to make much needed medicine available to the POW’s, was the order given to sign the document. It was a point of no-return for the POW’s who then became used for forced labour. The formula was simple – if you worked, you received food, if you did not, you would get no food.

Captivity

The shoes belonging to a POW who had been shot, left out to remind others not to disobey orders, rope used for torture

British POW’s made small lamps using cigarette tins, collecting coconuts to make oil for the lamps.

There are many recollections from the POW’s of how the local Chinese, including the elderly, would try to help them as they were marched through Singapore to work. Despite being beaten they would appear every day trying to give them morsels of food and drink.

By 1943, the 7,000 men left at Selarang Barracks were moved to Changi Gaol. The Changi Gaol had been built to hold about 600 people, with five or six to one-man cells this severe overcrowding, together with acute food and medicine shortages, meant death from malaria, dysentery and vitamin deficiencies became rife.

POW’s were made to dig tunnels and fox holes in the hills around Singapore as hideouts for the Japanese should the Allies return. Many POW’s believed they would then be killed; in fact when the Allies did recapture Singapore, the prison was simply handed over to them. After the war Changi Gaol, renamed Changi Prison, resumed its function as a civilian prison.

A piece of the original gaol wall

Stories from Changi Gaol

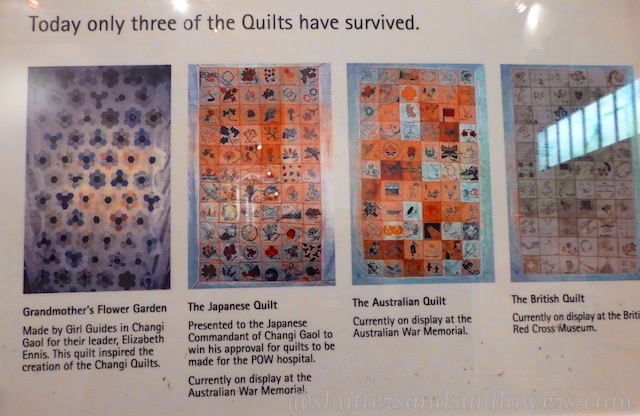

The Changi Quilts

The Changi quilts are a testament to the courage, ingenuity and perseverance of the female Changi internees. The quilt making was initiated by Canadian, Ethel Mulvaney, to alleviate boredom and frustration. More importantly it was a way to communicate with the male internees, as all other communication was forbidden. Women were given six-inch squares of rice sack cloth to embroider her name. Sown together, under the pretext of a gift, the Quilts were handed over to the civilian men for the POW hospital. Knowledge of the women’s well-being boosted the men’s morale.

Changi Embroidery Cloths

This souvenir cloth is similar to a piece that British POW, Augusta M Cuthbe, had women internees embroider their names on.

St Luke’s Chapel

In early 1942 Padre Fred Stallard, a chaplain in Roberts Hospital at Changi, obtained permission to convert a small room of Block 151 into a chapel. Built mainly be Australian prisoners this became St Luke’s Chapel.

The Chapel Altar Cloth

This 76cm2 piece of silk was used as the altar cloth in Changi Prison’s St George’s Chapel, during World War II. It fell into the hands of Singapore’s then Chief Postmaster, Geoffrey Carl Allen. He died in England but when his wife heard about the worldwide 50th anniversary celebrations of World War II she donated it and 5 years later it was sent to Singapore when the Changi Chapel Museum was being redeveloped.

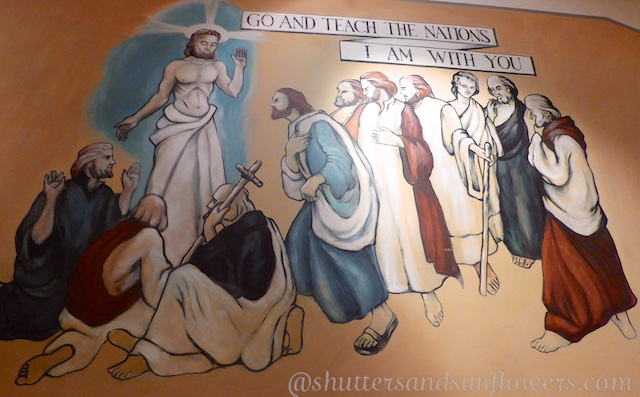

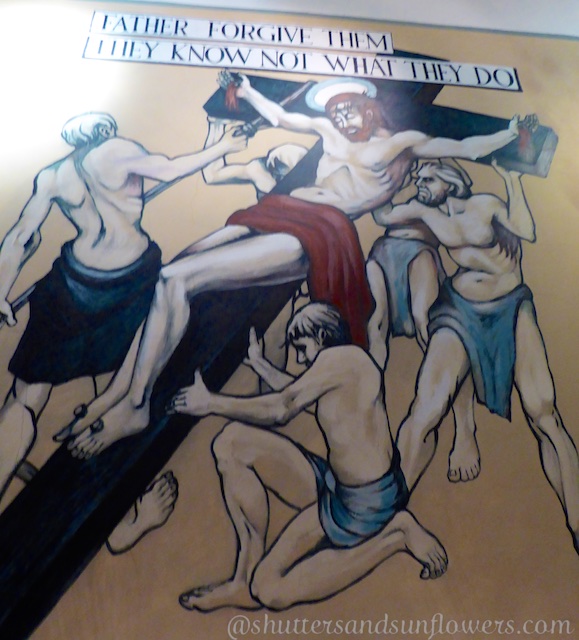

St Luke’s Chapel Murals

The wall murals in St Luke’s Chapel were painted by Stanley Warren who had been a commercial artist before the war. He had come to Changi Gaol hospital as a critically ill British POW and despite severe physical limitations was encouraged to paint murals on the chapel walls. Although paint was not readily available, with the aid of other prisoners, who unquestionably put themselves at risk, materials were gradually acquired. Crushed billiard cue chalk was used to produce blue. Warren began the first of the Changi Murals on 6 October 1942.

In August 1943 Robert Hospital was relocated to Selarang Barracks, and a new St Luke’s Chapel was set up, the original chapel was eventually converted into a store used by both the Japanese and the RAF. The walls were painted over and the murals concealed. In 1958 an RAF serviceman detected traces of color on the walls, layers of distemper were scraped off and the murals were once again revealed but no one knew the identity of the artist. The RAF Changi Magazine, ‘Tale Spin’, published pictures of them in an attempt to locate the artist. At the same time a book entitled ‘Churches of Captivity in Malaya’ was found in the Far East Air Force Educational Library revealing the name of the painter. In January 1959 Stanley Warren was found, he was an arts master at Sir William Collins Secondary School in North London. He was asked to return to Singapore in the early 1960’s to restore the murals.

Initially Stanley was very reluctant to return because of his horrific war time memories. However in December 1963, despite the great distress it caused him, Stanley went back. He became very dedicated to the restoration, returning to Changi again in July 1982 and May 1988, which was his final visit. He passed away in Bridport, England on 20 February 1992, his murals however remain a legacy forever.

In 1980 Changi Gaol was refurbished into a modern penal institution. By 2005 most of the original prison was demolished and a larger facility built. Today only a 180m stretch of the prison wall facing Upper Changi Road remains. The iconic main gate of the prison, two guard towers and the clock from the original clock tower have been preserved at the original site.

A visit to the Changi Museum and Chapel is distressing but very moving, a testament to the courage and determination of people bravely overcoming great adversity. It’s well worth including on your itinerary whilst visiting Singapore.

Two of my uncles were incarcerated in Changi in 1942. One went into the cloth trade in the UK but he could never face off with the Japanese in cloth negotiations. The horror and abuse he had faced from his torturers had inflicted upon him a lifelong hatred of the Japs.My mother said neither of her brothers were the same ever again after starvation rations had caused sever neurological injury. They had been lucky getting off France at Dunkirk but unlucky not getting out of Singapore.. The saddest fact was that had the British put patrols out in the North of Singapore the Japanese presence could have been detected and the superior numbers of British troops would have beaten a very aggressive enemy.

Thank you for telling me about your family’s story, albeit a difficult one. They certainly were very cruel times. Standing in Changi, even today, the sense of terror somehow still permeates the air. Although we’ve come along way since 1945 it’s tragic that despite all that suffering similar inhumanity and injustice is still occurring in different parts of the world. If only mankind could put away prejudice and greed……

Its staggeringly shocking just what humans can inflict upon each other, yet just how resourceful and compassionate, the will to survive can be. The sadness is, the World is seemingly no less violent, and so little has changed in the ensuing years, hardly a lasting legacy to better things. Christopher Bater.

Indeed, how little we have learnt. Thank you for taking the time to comment

My father Percy Hebert British Actor was in Changi for the duration of the war in solitary for 6 months . One of his first films was Bridge on the River Kwai where Director David Lean paid him additional money as a consultant as he had been a POW there . He went on to have a major film career despite suffering from acute PTSD and is a testimony to resilience and the will to live despite my mother receiving a telegram saying he was missing presumed dead until he showed up at my grandmothers house where my mother was with her new fiancee weighing 90 pounds emaciated but alive- In a moment she had to make the decision of her life and chose to marry my father a seminal moment for everyone! – Sadly his life was cut short due to the accumulative diseases that were left untreated towards the end of his life having been in Changi however he had a stellar film career for over 4 decades – I went on to develop mental health clinics as a doctor of psychology as a result of the experiences of the impact of PTSD in families . He was an amazing role model for a father and miss him dearly. He never spoke about the tortures but wrote a book which we published called Time Will Pass Johnny – was the only way he could express such grueling events ( we hope to formerly publish one day ) . Later Japanese Government decades later sent POWS and a check to my mother as my father had died by then for $14, 000 which she gave to my sister and i as she did not want any part of it – Such is this thumb nail story of this part of his life- https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Trivia/TheBridgeOnTheRiverKwai

Thank you so much fir sharing this incredible, inspiring story, I soooooo appreciate you taking the time to explain this deeply moving piece of personal history

Around 1975 I watched a movie on tv in New Zealand about the women who were imprisoner by the Japanese in Changi. In August of that year My husband in the NZ army was posted to Singapore accompanied by myself and our 2 children. On a wives club trip we saw those original murals in the old barracks block and the bullet marks up the end of the building. We also visited a little church and spoke to an elderly nun who told us of her experience as a prisoner of the Japanese and the story she told was the same story I had seen in that movie. I would love to find the name of that movie so I could watch it again. It was not Paradise Road. The movie showed the women marching into the prison and as they neared the gates they sang and as the passed through the gates they sang their names so the men could hear. Does anyone know the name of that movie please.

Thank you for reaching out Lynne. I’ll try to find out!